Understanding Trauma After Hospitalization

Psychiatric hospitalization can be stressful and even traumatic for some. Themes of limited freedom, coercion, and fear can be a reality in some hospitals.

Sometimes, patients are admitted to a psych ward against their will due to certain mental health disorders or potential harm to themselves or others. Other times, involuntary hospitalization may be related to substance use issues, and the individual is taken to a treatment center.

Whether due to mental health or drug and alcohol addiction, simply being locked in a room as a patient can be terrifying. Other causes of hospitalization-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) include being put in restraints and being forced to take medicine.

Less commonly reported but also a serious cause of PTSD symptoms is physical abuse by staff.

Online Therapy or Virtual Consultations

What Percentage of Psychiatric Patients Experience Trauma?

Psychiatric hospitalization can be negatively experienced, and some studies even show a high frequency of traumatic occurrences.

Hospital stays can increase symptoms of depression and exacerbate anxiety disorder.

It is important to note that not every negative experience is traumatic. Trauma usually consists of prolonged and repeated exposure or threats of violence.

A study published in the National Library of Medicine reported that 69% of patients perceived their hospitalization visit as traumatic. Women and homemakers were also more likely to be traumatized than other individuals.

Another study published that “involuntary commitment to a psychiatric unit can be a traumatic experience for some patients”. And further studies agree with the claim that the involuntary nature of psych wards can cause “increased levels of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms”.

What Is Post-hospital Syndrome?

Post Hospital Syndrome, or PHS, is the decline in physical and mental well-being after being discharged from the hospital.

Symptoms of PHS include:

- Physical weakness

- Fatigue

- Confusion

- Cognitive impairment

- Emotional distress

These symptoms can lead to an increased risk of complications or readmission to the hospital. Therefore, it is important to utilize the support of family, friends, and a trained professional.

PHS can last from a few weeks to months, depending on individual factors.

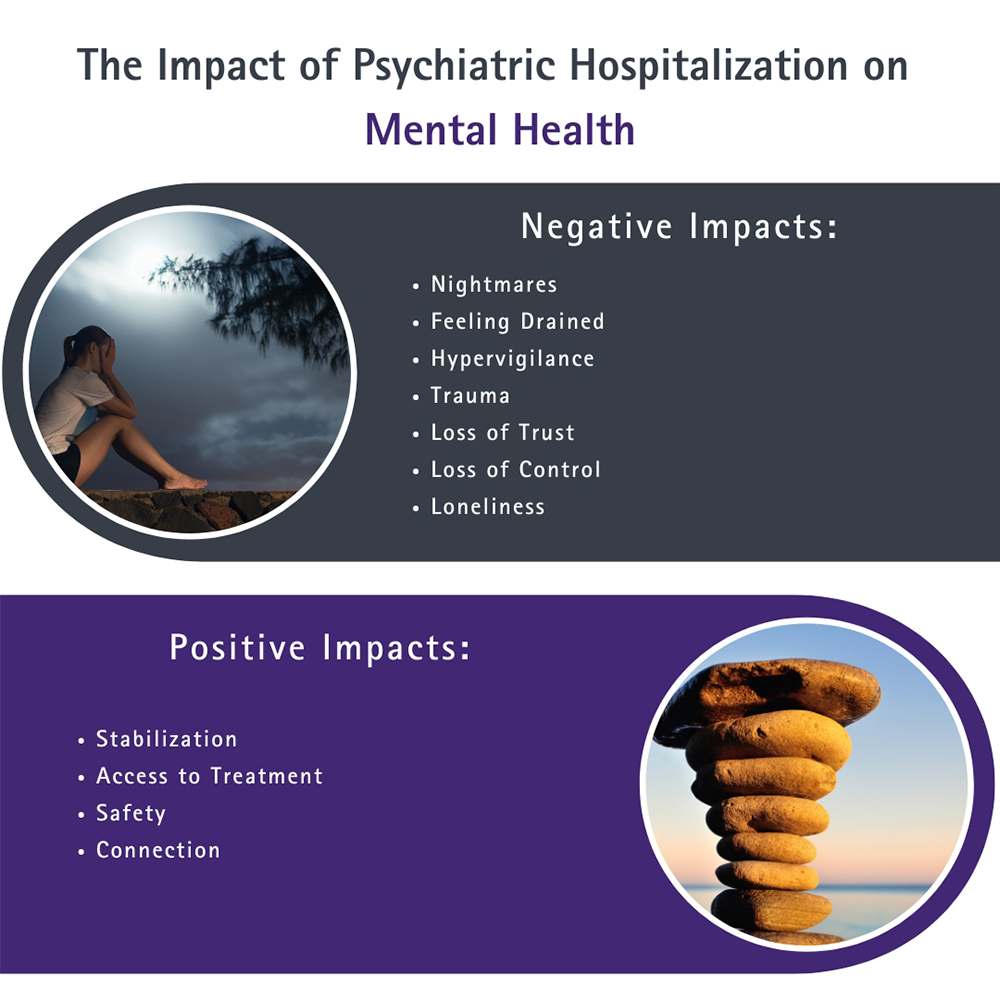

The Impact of Psychiatric Hospitalization on Mental Health

Psychiatric hospitalization can have a profound impact on mental health, both positive and negative.

Negative effects of psychiatric hospitalization include:

- Nightmares

- Feeling drained

- Hypervigilance

- Trauma

- Loss of trust

- Loss of control

- Loneliness

Not everyone will experience all of these effects. If you experience any of the above, talk to one of our trauma counselors in West Palm Beach.

For more information about our counselors or to schedule an appointment with a trauma therapist, call the therapy center.

(561) 363-7994Treatment Options for Trauma

After leaving the hospital, it is important to follow certain steps to ensure your physical, mental, and behavioral health.

Some important steps after any type of trauma include:

- Remember to get adequate rest, eat healthy food, and get the appropriate amount of exercise for your medical condition.

- Connect with family, friends, support groups, and trained professionals for support in your recovery.

- Minimize stress, learn relaxation techniques such as meditation, deep breathing, and journaling, and participate in activities you enjoy.

- Stay in touch with your therapist. Let them know how you are feeling and if you have any concerns.

Each person may require their own individualized self-care routine based on situation and needs. You and your therapist can create a plan for self-care after psychiatric hospitalization.

Types of Trauma-Informed Therapy

Trauma counseling after psychiatric hospitalization can include:

- Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR): Using bilateral stimulation such as eye movement, tapping, or auditory stimulation to activate both sides of the brain for processing.

- Cognitive processing therapy (CPT): Identify and challenge patterns of negative thought for a more positive perspective.

- Narrative exposure therapy (NET): Create a cohesive narrative of your experience to challenge your perspective.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT): Identify cognitive distortions that are causing negative feelings and behaviors.

Your therapist will create a safe and supportive environment and provide further information on each form of mental health treatment to help you make the choice of which one is right for you.

Benefits of Trauma Mental Health Treatment in WPB

A trained therapist specializing in trauma can help you:

- Have a safe and nonjudgemental space to share your feelings about your experience.

- Process your trauma and make better sense of what you experienced during your hospitalization.

- Develop coping skills to deal with this and other challenges in the future.

- Rebuild trust in yourself, others, and the world.

- Develop a deeper understanding of yourself.

- Regain control of your life.

Our top-rated therapists specialize in trauma counseling and can help you improve your mental well-being after trauma from psychiatric hospitalization.

Recovery is not linear, and challenges may arise.

If you would like some help with coping outside of therapy, consider the following hotlines available 24/7:

- National Suicide Prevention Lifeline: 988

- Crisis Text Line: Text HOME to 741741 from anywhere in the US, anytime, about any type of crisis.

- The Trevor Project: 1-866-488-7386 This hotline is specifically for LGBTQ youth in crisis.

If you experience psych ward trauma – we are here to support you. Take control of your well-being and start your healing journey toward healing today. Contact us for a confidential consultation and discover the power of professional trauma therapy in West Palm Beach. We offer outpatient services across the Palm Beaches.

Sources:

The American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 163, no. 8, 2006, pp. 1424–1429

The American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 161, no. 12, 2004, pp. 2219–2224.